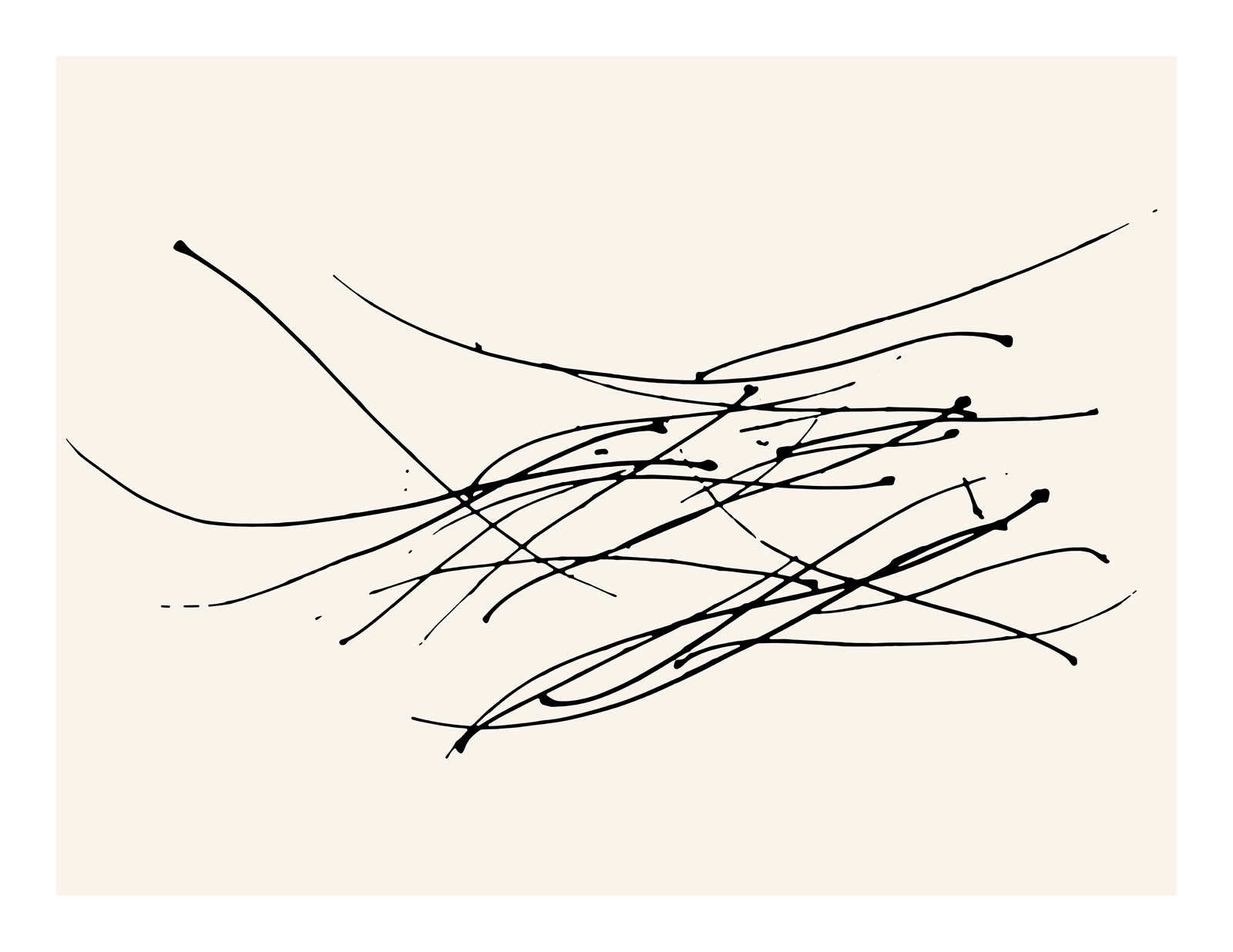

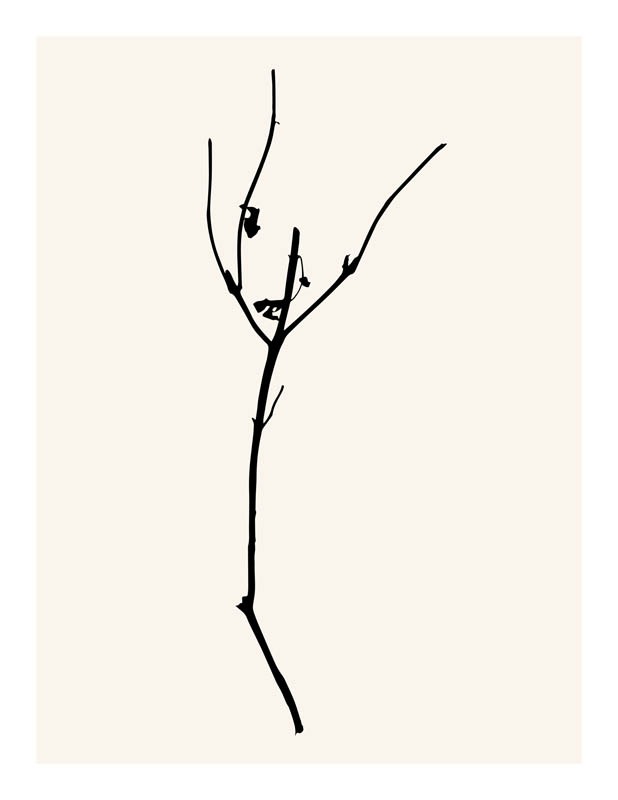

Finding My Way (2023)

Archival Print on Cotton Rag

44 x 64 Inches

44 x 64 Inches

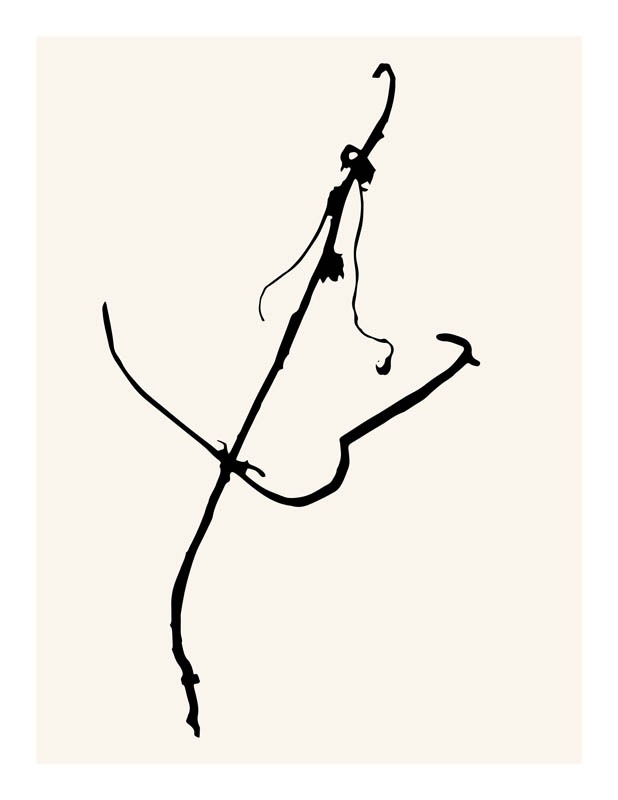

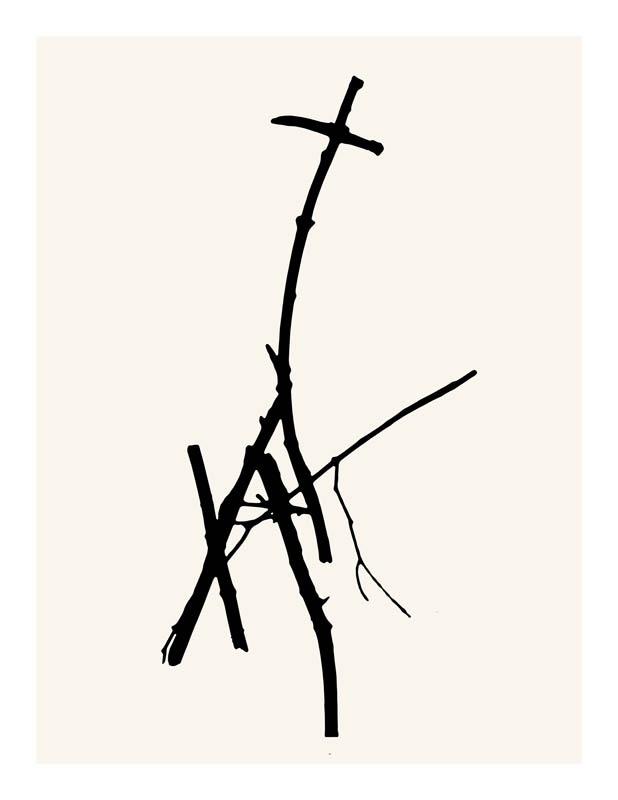

Casting Sticks

Casting Sticks began as a series of photographs of fallen branches on snow— the snow itself was not significant other than it allowed me to see shapes that might have otherwise gone unnoticed. Using a digital process that mimics lith printing—an infectious development technique that intensifies dark areas to create high-contrast prints resembling charcoal drawings—I created these stark, monochromatic compositions.

Initially, I considered these images through the lens of divination, perhaps influenced by my grandmother, Jessie Scott Robertson, who read tea leaves and claimed Romani blood. This led me to explore various forms of divination, from runes and cleromancy (casting lots) to xylomancy (interpreting wood patterns). Yet, the deeper I went, the less convinced I was that this was the direction of the work was leading me. However, as I began a new body of work, The Naming of Things, which will explore how language shapes our perception of the natural world, I came to see Casting Sticks as a bridge between my earlier series, Walking, and this latest inquiry.

Collectively, my work over the past few years has been documenting my changing relationship with nature, but it has also been a catalyst for that change—a self-fulfilling process. Or, as a Buddhist might say, the goal becomes the path. The work is both an expression of and an inquiry into my relationship with nature.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau proposed that as humanity progressed from pictographic writing to the modern alphabet, it moved from savagery to civilization, from chaos to order. Even if this were true—and the work of David Graeber and David Wengrow in The Dawn of Everything suggests otherwise—I question whether this shift was truly progress. It seems instead to have contributed to a human-centered worldview that distances us from nature. Even as recently as the early 20th century, critics like Guillaume Apollinaire urged artists to dominate nature rather than be deferential to it. This lineage of thought—language as mastery, power, civilization, and superiority—has not only deepened our alienation from the world that sustains us but has also sown the seeds of racism and eugenics.

I now see Casting Sticks as a meditation on the origins of writing and the part it played in our self-exclusion from Eden. By contemplating its origins and evolution, I may glimpse what has been lost.

Initially, I considered these images through the lens of divination, perhaps influenced by my grandmother, Jessie Scott Robertson, who read tea leaves and claimed Romani blood. This led me to explore various forms of divination, from runes and cleromancy (casting lots) to xylomancy (interpreting wood patterns). Yet, the deeper I went, the less convinced I was that this was the direction of the work was leading me. However, as I began a new body of work, The Naming of Things, which will explore how language shapes our perception of the natural world, I came to see Casting Sticks as a bridge between my earlier series, Walking, and this latest inquiry.

Collectively, my work over the past few years has been documenting my changing relationship with nature, but it has also been a catalyst for that change—a self-fulfilling process. Or, as a Buddhist might say, the goal becomes the path. The work is both an expression of and an inquiry into my relationship with nature.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau proposed that as humanity progressed from pictographic writing to the modern alphabet, it moved from savagery to civilization, from chaos to order. Even if this were true—and the work of David Graeber and David Wengrow in The Dawn of Everything suggests otherwise—I question whether this shift was truly progress. It seems instead to have contributed to a human-centered worldview that distances us from nature. Even as recently as the early 20th century, critics like Guillaume Apollinaire urged artists to dominate nature rather than be deferential to it. This lineage of thought—language as mastery, power, civilization, and superiority—has not only deepened our alienation from the world that sustains us but has also sown the seeds of racism and eugenics.

I now see Casting Sticks as a meditation on the origins of writing and the part it played in our self-exclusion from Eden. By contemplating its origins and evolution, I may glimpse what has been lost.

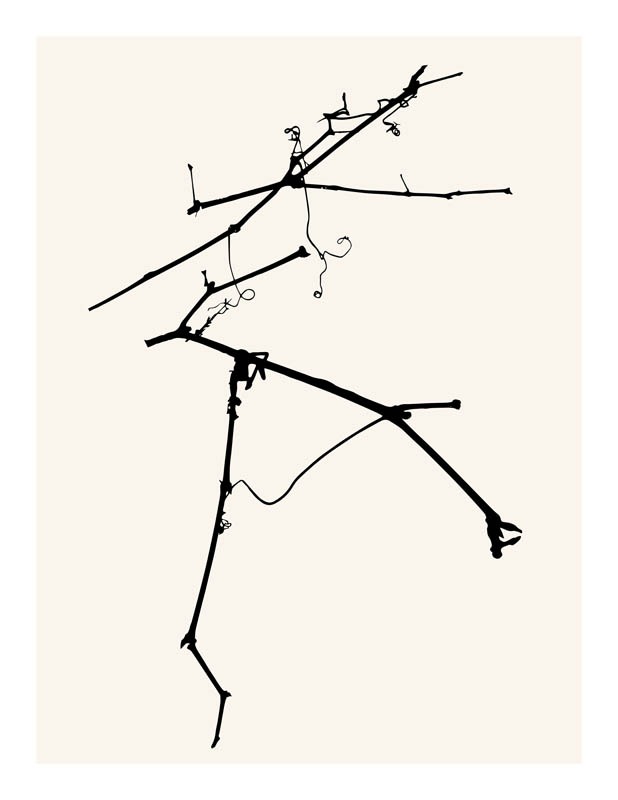

What if the Wind were a Witch (2024)

Archival Print on Cotton Rag

34 x 44 Inches

34 x 44 Inches

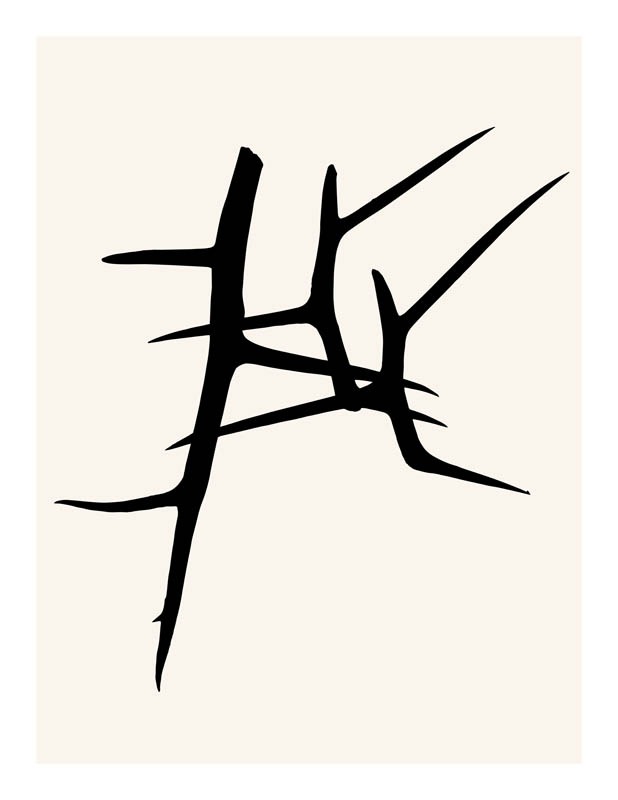

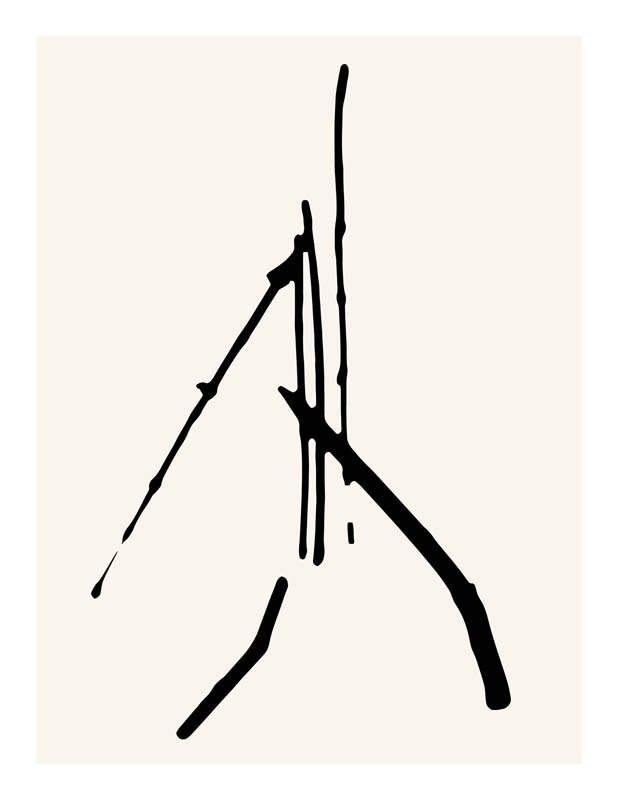

What if the Wind were a Witch

Perhaps it is. After all, we can’t see the wind itself; we only see what it touches, moves and stirs. The same is true for ideas, insight, fate, and even love! There are many things we can’t see directly but whose effects can be experienced.

Natural forces, imperceptible to our five senses, exert their presence in the world around us. This image asks us to trust what we cannot see. Just as the wind’s invisible energy reveals itself in the swaying branches, unseen powers weave an invisible thread through our lives; joining, connecting, and influencing events in subtle, magical ways

Perhaps it is. After all, we can’t see the wind itself; we only see what it touches, moves and stirs. The same is true for ideas, insight, fate, and even love! There are many things we can’t see directly but whose effects can be experienced.

Natural forces, imperceptible to our five senses, exert their presence in the world around us. This image asks us to trust what we cannot see. Just as the wind’s invisible energy reveals itself in the swaying branches, unseen powers weave an invisible thread through our lives; joining, connecting, and influencing events in subtle, magical ways

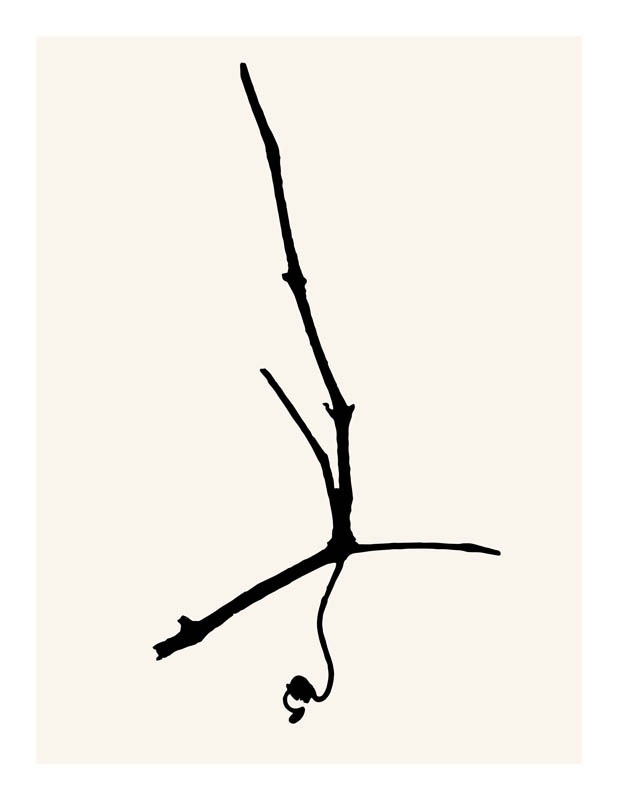

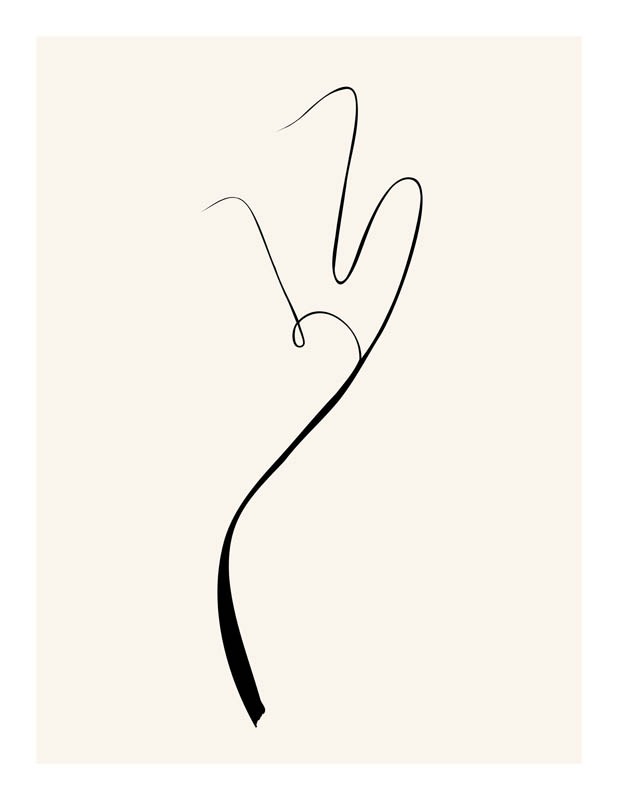

Taking the Plunge (2024)

Archival Print on Cotton Rag

34 x 44 Inches

34 x 44 Inches

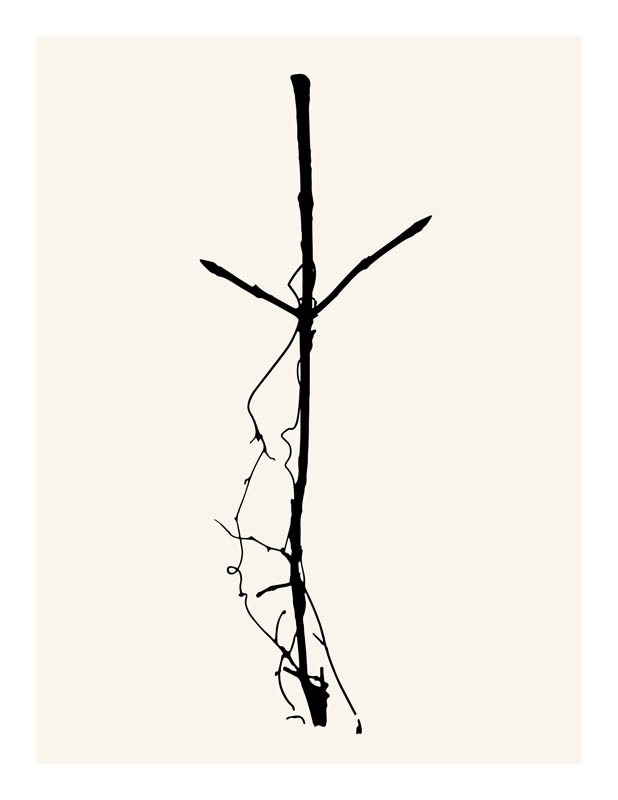

Pilgrimage of Surrender (2024)

Archival Print on Cotton Rag

34 x 44 Inches

34 x 44 Inches

The happy Drunk (2023)

Archival Print on Cotton Rag

34 x 44 Inches

34 x 44 Inches

The collision of joy (2024)

Archival Print on Cotton Rag

34 x 44 Inches

34 x 44 Inches

tip-toe through the whispers (2024)

Archival Print on Cotton Rag

34 x 44 Inches

34 x 44 Inches

the nervous kind (2024)

Archival Print on Cotton Rag

34 x 44 Inches

34 x 44 Inches

curving by design (2024)

Archival Print on Cotton Rag

34 x 44 Inches

34 x 44 Inches

Triumph (2024)

Archival Print on Cotton Rag

34 x 44 Inches

34 x 44 Inches